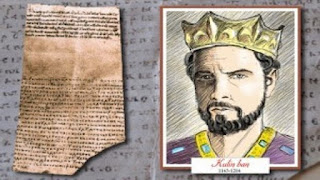

Kulin (d. c. November 1204) was the

Ban of Bosnia from 1180 to 1204, first as a vassal of the Byzantine Empire and

then of the Kingdom of Hungary, but his state was defacto independent. He was

one of Bosnia's most prominent and notable historic rulers and had a great

effect on the development of early Bosnian history.

One of his most noteworthy diplomatic

achievements is widely considered to have been the signing of the Charter of

Ban Kulin, which encouraged trade and established peaceful relations between

Dubrovnik and his realm of Bosnia.His son, Stjepan Kulinić succeeded him as

Bosnian Ban. Kulin founded the House of Kulinić. Kulin's origin is unknown. His

sister was married to Miroslav of Hum, the brother of Serbian Grand Prince Stefan

Nemanja (r. 1166–1196).

Byzantine Emperor Manuel I Komnenos

(1143–1180) was at that time the overlord of Bosnia.[6] In 1180, when Komnenos

died, Stefan Nemanja and Kulin asserted independence of Serbia and Bosnia,

respectively. His rule is often remembered as being emblematic of Bosnia's

golden age, and he is a common hero of Bosnian national folk tales. Under him,

the "Bosnian Age of Peace and Prosperity" would come to exist. Bosnia

was completely autonomous and mostly at peace during his rule.

War

against Byzantium

In 1183, he led his troops with the

forces of the Kingdom of Hungary under King Béla and the Serbs under Stefan

Nemanja, who had just launched an attack on the Byzantine Empire. The cause of

the war was Hungary's non-recognition of the new emperor, Andronikos Komnenos.

The united forces met little resistance in the eastern Serbian lands - the

Byzantine squadrons were fighting among themselves as the local Byzantine

commanders Alexios Brannes supported the new Emperor, while Andronikos Lapardes

opposed him - and deserted the Imperial Army, going onto adventures on his own.

Without difficulties, the Byzantines

were pushed out of the Morava Valley and the allied forces breached all the way

to Sofia, raiding Belgrade, Braničevo, Ravno, Niš and Sofia itself.

Bogomils

In 1199, Serbian prince Vukan Nemanjić

informed the Pope, Innocent, of heresy in Bosnia. Vukan claimed that Kulin, a

heretic, had welcomed the heretics whom Bernard of Split had banished, and

treated them as Christians. In 1200, the Pope wrote a letter to Kulin's

suzerain, the Hungarian King Emeric, warning him that “no small number of

Patarenes” had gone from Split and Trogir to Ban Kulin where they were warmly

welcomed, and told him to “Go and ascertain the truth of these reports and if

Kulin is unwilling to recant, drive him from your lands and confiscate his

property.”

Kulin replied to the Pope that he did

not regard the immigrants as heretics, but as Catholics, and that he was

sending a few of them to Rome for examination, and also invited that a Papal

representative be sent to investigate. Unconvinced, the Pope sent his legates

to Bosnia to interrogate Kulin and his subjects about religion and life, and if

indeed heretical, correct the situation through a prepared constitution.

The Pope wrote to Bernard in 1202 that

"a multitude of people in Bosnia are suspected of the damnable heresy of

the Cathars." The two legates sent by the Pope went through the country of

Bosnia and interrogated the clergy.

Bilino

Polje abjuration

Not only did Casamaris listen to his

informants’ answers, but where they were in error, he would have taught them

correct doctrine, in line with Innocent’s directive. John must have convinced

himself that he had fulfilled Innocent’s command to correct the krstjani,

because the “Confessio” (Abjuration) signed at Bilino Polje by seven priors of

the Krstjani church on 8 April 1203, makes no mention of errors.

The same document was brought to

Budapest, 30 April by Casamaris and Kulin and two abbots, where it was examined

by the Hungarian King and the high clergy. Kulin’s son Stefan, during a later

meeting, agreed that if the Bosnians violated the agreement, they would pay a

heavy fine of 1,000 marks.

On the surface, the “Confessio”

concerned church organization and practices. The monks renounced their schism

with Rome and agreed to accept Rome as the mother church. They promised to

erect chapels with altars and crucifixes, where they would have priests who

would say Mass and dispense Holy Communion at least seven times a year on the

main feast days.

The priests would also hear confession

and give penances. The monks promised to chant the hours, night and day, and to

read the Old Testament as well as the New. They would follow the Church’s

schedule of fasts, as well as their own regimen. They also agreed to stop

calling themselves krstjani—which had been their exclusive privilege—lest they

cause pain to other Christians. They would wear special, uncolored robes,

closed and reaching the ankles. In addition they were to have graveyards next

to the church, where they would bury their brethren and any visitors who

happened to die there.

Women members of the order were to

have special quarters away from the men and to eat separately; nor could they

be seen talking alone with a monk, lest they cause scandal. The abbots also

agreed not to offer lodging to manicheans or other heretics. Finally, upon the

death of the head of their order (magister), the abbots, after consultation

with their fellow monks, would submit their choice to the Pope for his

approval. As for the Bosnian Catholic diocese itself, John advised Innocent

that they needed to break the hold of the Slavonic bishop who had ruled the

Bosnian church up to then, and to appoint three or four Latin bishops, since

Bosnia was a large country (“ten days’ walk”).

After the “Confessio” was approved by

King Emmerich, John de Casamaris, in a letter to Innocent, refers to “the

former Patarenes.” Obviously, he thought that he had converted the krstjani,

but he was wrong. Partly due to Rome’s complacency (caused by Casamaris’s

feelings of success) and the Pope’s failure to appoint Latin bishops, as John

had suggested, the heretical movement grew stronger over the next few decades,

uniting with remnants of the old native Catholic church. Together they formed a

national, heretical church which survived crusades and threats of crusades

until the mid-fifteenth century, when it gradually vanished in the face of the

Ottoman takeover

Charter

of Ban Kulin

The Charter of Ban Kulin was a trade

agreement between Bosnia and the Republic of Ragusa that effectively regulated

Ragusan trade rights in Bosnia written on 29 August 1189. It is one of the

oldest written state documents in the Balkans and is among the oldest

historical documents written in Bosnian Cyrillic. The charter is of great

significance in both Serbian and Bosnian national pride and historical

heritage.

Death

After the death of Ban Kulin in 1204,

the Bosnian throne was succeeded by his son Stjepan Kulinić (often referred to

in English as Stephen Kulinić).

Marriage

and children

Kulin

married Vojislava, with whom he had two sons:

Stephen Kulinić, the following Ban of

Bosnia

A son that went with the Pope's emissaries

in 1203 to explain heresy accusations against Kulin

Legacy

and folklore

As a founder of first defacto

independent Bosnian state, Kulin was and still is highly regarded among

Bosnians. Even today Kulin's era is regarded as one of the most prosperous

historical eras, not just for Bosnian medieval state and its feudal lords, but

for the common people as well, whose lasting memory of those times is kept in

Bosnian folklore, like an old folk proverb with significant meaning: "Od

kulina Bana i dobrijeh dana" ("English: Since Kulin Ban and those

good ol' days").

Accordingly, in today's Bosnia and

Herzegovina, many streets and town squares, as well as cultural institutions,

and non-governmental organizations, bear Kulin's name, while numerous

culturally significant events, manifestation, festivals and anniversaries are held

in celebration of his life and deeds

Nema komentara:

Objavi komentar