This is official blog page of BLUE SKY MOSTAR media & publishing. We are a studio for creating video content from tourism, history, sports and other interesting content. Our headquarters are in Mostar, Bosnia and Herzegovina. We are part of the BLUE SKY group along with Agency for Tourism Travel in Bosnia and Herzegovina and Accommodation in Mostar.

Prikazani su postovi s oznakom bosnian kingdom. Prikaži sve postove

Prikazani su postovi s oznakom bosnian kingdom. Prikaži sve postove

subota, 9. prosinca 2017.

petak, 1. prosinca 2017.

Tešanj Castle: One of Oldest and Biggest in Bosnia and Herzegovina

The old city of Tešanj, where the

castle is located, was built on a hill in the valley, along the river Tešanj,

on a steep and partly isolated cliff of a hill, hardly accessible from the

three sides of the town of Tešanj in the north of B&H. This beauty on the

hill of Tešanj has existed for already three thousand years.

This fortified settlement from the

Medieval period belongs to a group of larger, fortified towns on the plateau,

specifically built on the top of a rocky hill from which you can see the whole

city of Tešanj in a valley.

The castle is considered to have been

built during the Bronze Age, and until today, has fallen into a kind of

oblivion and there was no special interest in one of the oldest fortresses in

B&H today.

The Tešanj castle, after the one in

Jajce, is considered to be one of the biggest fortresses in B&H.

However, it is important to note that

in the 1970’s its multiple protection that lasts until today began.

The fortress certainly provokes the

interest of passers by, tourists, and a team from Anadolija decided to visit

this somehow forgotten fortress, which is considered to be one of the oldest

buildings in B&H.

”Tešanj,

with its fortress, developed into a ravine on the slopes of the hills, and in

the middle a very interesting defensive point has been raised, a hill, from

which it is obvious that it is from the Bronze Age and to the present day

developed into a fortified object or fortress”, said professor Mirza Hasan

Ćeman.

He said that evidence from the period

of the Bronze Age shows that there were settlements of this narrow territory

from the second millennium BC until today.

Speaking about the history of Tešanj

and its fortress, Ćeman explains that the castle developed into a feudal

fortified building during the Middle Ages that later grew into a residential

building of the feudal nobility.

”It

never developed into a significant administrative center. However, in the 15th

century it came under the role of the brother of the Bosnian King Stjepan Tomaš

Radivoje Krstić”, he

explained.

The castle was under Ottoman rule

since 1463, but it is not known whether it was under an Ottoman military

garrison.

”It

is not clear whether in the 15th century there was a settlement at the foot of

the fortress, but it can be assumed, because the Franciscans were obviously

there for a population”,

said Ćeman.

He thinks that the castle came under

permanent Ottoman rule in 1520 and a permanent military garrison was set up.

Over the next century the castle was

repaired, restored and enlarged in accordance with the political and military

developments and economic opportunities of the Bosnian Pashaluk.

”The

Tešanj castle existed in the Middle Ages as well, and it was taken over by the

Turks. I think, based on personal research from the field, that during the time

of Sultan Sulejman the Magnificent an entrance was erected, which ensured

entrance into the castle”,

explained Ćeman.

The Professor explained that the

Austrian Army led by Prince Eugene of Savoy attacked and took the castle in

1697.

”This

heavy siege of the Tešanj castle and the city ended after three days of

unsuccessful attacks. The Autrian Army retreated in the direction of Slavonia”, said Ćeman.

Speaking about its importance today,

the Professor explained that at the end of the 18th and beginning of 19th

century, its significance weakened.

”With

the arrival of Austria it has been sinking into oblivion. New techniques of

warfare and new funds minimized the importance of the castle, although during

WWII, the same object was taken by the Independent Croatian State and on 9

September, in a very specific way, it was taken over by the unit of the

People’s Liberation Army”,

explained Ćeman.

Since then the castle has again fell

into oblivion, and only in the 1970’s did its multiple protection begin and

lasts until today.

The castle has been preserved to this

day thanks to the interventions during the 1960’s, when one tower was protected

from decomposition as a result of lightning.

It has survived many wars, conquerors,

and is still standing proud on a hill in Tešanj and defies time and its

enemies.

srijeda, 29. studenoga 2017.

srijeda, 15. studenoga 2017.

King town Bobovac

Bobovac is a fortified city of

medieval Bosnia and Herzegovina. It is located near today's Vareš and the

village of Borovica.

The city was built during the reign of

Stephen II, Ban of Bosnia, and was first mentioned in a document dating from

1349. It shared the role of seat of the rulers of Bosnia with Kraljeva

Sutjeska, however Bobovac was much better fortified than the other.

Bosnian King Stephen Tomašević moved

the royal seat to Jajce during his war with the Ottoman Empire. The Ottomans

invaded the city in 1463. Its fall hastened the Ottoman conquest of Bosnia.

Bobovac is now a protected cultural

site.

Bobovac contained the crown jewels of Bosnia as

well as being the burial site for some of the kings of Bosnia. Nine skeletons

have been found in the five tombs located in the mausoleum. The identified

skeletons belong to kings Dabiša, Ostoja, Ostojić, Tvrtko II and Thomas. It is

assumed that one of the remaining skeletons belongs to the last king,

Tomašević, decapitated in Jajce on the order of Mehmed the Conqueror. Only one

of the skeletons, found next to that of King Tvrtko II, is female and assumed

to belong to Tvrtko II's wife, Queen Dorothy.

nedjelja, 12. studenoga 2017.

ponedjeljak, 6. studenoga 2017.

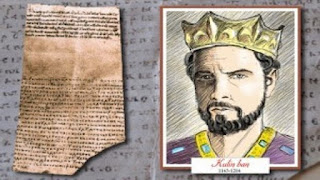

Ban Kulin (Duke of Bosnia)

Kulin (d. c. November 1204) was the

Ban of Bosnia from 1180 to 1204, first as a vassal of the Byzantine Empire and

then of the Kingdom of Hungary, but his state was defacto independent. He was

one of Bosnia's most prominent and notable historic rulers and had a great

effect on the development of early Bosnian history.

One of his most noteworthy diplomatic

achievements is widely considered to have been the signing of the Charter of

Ban Kulin, which encouraged trade and established peaceful relations between

Dubrovnik and his realm of Bosnia.His son, Stjepan Kulinić succeeded him as

Bosnian Ban. Kulin founded the House of Kulinić. Kulin's origin is unknown. His

sister was married to Miroslav of Hum, the brother of Serbian Grand Prince Stefan

Nemanja (r. 1166–1196).

Byzantine Emperor Manuel I Komnenos

(1143–1180) was at that time the overlord of Bosnia.[6] In 1180, when Komnenos

died, Stefan Nemanja and Kulin asserted independence of Serbia and Bosnia,

respectively. His rule is often remembered as being emblematic of Bosnia's

golden age, and he is a common hero of Bosnian national folk tales. Under him,

the "Bosnian Age of Peace and Prosperity" would come to exist. Bosnia

was completely autonomous and mostly at peace during his rule.

War

against Byzantium

In 1183, he led his troops with the

forces of the Kingdom of Hungary under King Béla and the Serbs under Stefan

Nemanja, who had just launched an attack on the Byzantine Empire. The cause of

the war was Hungary's non-recognition of the new emperor, Andronikos Komnenos.

The united forces met little resistance in the eastern Serbian lands - the

Byzantine squadrons were fighting among themselves as the local Byzantine

commanders Alexios Brannes supported the new Emperor, while Andronikos Lapardes

opposed him - and deserted the Imperial Army, going onto adventures on his own.

Without difficulties, the Byzantines

were pushed out of the Morava Valley and the allied forces breached all the way

to Sofia, raiding Belgrade, Braničevo, Ravno, Niš and Sofia itself.

Bogomils

In 1199, Serbian prince Vukan Nemanjić

informed the Pope, Innocent, of heresy in Bosnia. Vukan claimed that Kulin, a

heretic, had welcomed the heretics whom Bernard of Split had banished, and

treated them as Christians. In 1200, the Pope wrote a letter to Kulin's

suzerain, the Hungarian King Emeric, warning him that “no small number of

Patarenes” had gone from Split and Trogir to Ban Kulin where they were warmly

welcomed, and told him to “Go and ascertain the truth of these reports and if

Kulin is unwilling to recant, drive him from your lands and confiscate his

property.”

Kulin replied to the Pope that he did

not regard the immigrants as heretics, but as Catholics, and that he was

sending a few of them to Rome for examination, and also invited that a Papal

representative be sent to investigate. Unconvinced, the Pope sent his legates

to Bosnia to interrogate Kulin and his subjects about religion and life, and if

indeed heretical, correct the situation through a prepared constitution.

The Pope wrote to Bernard in 1202 that

"a multitude of people in Bosnia are suspected of the damnable heresy of

the Cathars." The two legates sent by the Pope went through the country of

Bosnia and interrogated the clergy.

Bilino

Polje abjuration

Not only did Casamaris listen to his

informants’ answers, but where they were in error, he would have taught them

correct doctrine, in line with Innocent’s directive. John must have convinced

himself that he had fulfilled Innocent’s command to correct the krstjani,

because the “Confessio” (Abjuration) signed at Bilino Polje by seven priors of

the Krstjani church on 8 April 1203, makes no mention of errors.

The same document was brought to

Budapest, 30 April by Casamaris and Kulin and two abbots, where it was examined

by the Hungarian King and the high clergy. Kulin’s son Stefan, during a later

meeting, agreed that if the Bosnians violated the agreement, they would pay a

heavy fine of 1,000 marks.

On the surface, the “Confessio”

concerned church organization and practices. The monks renounced their schism

with Rome and agreed to accept Rome as the mother church. They promised to

erect chapels with altars and crucifixes, where they would have priests who

would say Mass and dispense Holy Communion at least seven times a year on the

main feast days.

The priests would also hear confession

and give penances. The monks promised to chant the hours, night and day, and to

read the Old Testament as well as the New. They would follow the Church’s

schedule of fasts, as well as their own regimen. They also agreed to stop

calling themselves krstjani—which had been their exclusive privilege—lest they

cause pain to other Christians. They would wear special, uncolored robes,

closed and reaching the ankles. In addition they were to have graveyards next

to the church, where they would bury their brethren and any visitors who

happened to die there.

Women members of the order were to

have special quarters away from the men and to eat separately; nor could they

be seen talking alone with a monk, lest they cause scandal. The abbots also

agreed not to offer lodging to manicheans or other heretics. Finally, upon the

death of the head of their order (magister), the abbots, after consultation

with their fellow monks, would submit their choice to the Pope for his

approval. As for the Bosnian Catholic diocese itself, John advised Innocent

that they needed to break the hold of the Slavonic bishop who had ruled the

Bosnian church up to then, and to appoint three or four Latin bishops, since

Bosnia was a large country (“ten days’ walk”).

After the “Confessio” was approved by

King Emmerich, John de Casamaris, in a letter to Innocent, refers to “the

former Patarenes.” Obviously, he thought that he had converted the krstjani,

but he was wrong. Partly due to Rome’s complacency (caused by Casamaris’s

feelings of success) and the Pope’s failure to appoint Latin bishops, as John

had suggested, the heretical movement grew stronger over the next few decades,

uniting with remnants of the old native Catholic church. Together they formed a

national, heretical church which survived crusades and threats of crusades

until the mid-fifteenth century, when it gradually vanished in the face of the

Ottoman takeover

Charter

of Ban Kulin

The Charter of Ban Kulin was a trade

agreement between Bosnia and the Republic of Ragusa that effectively regulated

Ragusan trade rights in Bosnia written on 29 August 1189. It is one of the

oldest written state documents in the Balkans and is among the oldest

historical documents written in Bosnian Cyrillic. The charter is of great

significance in both Serbian and Bosnian national pride and historical

heritage.

Death

After the death of Ban Kulin in 1204,

the Bosnian throne was succeeded by his son Stjepan Kulinić (often referred to

in English as Stephen Kulinić).

Marriage

and children

Kulin

married Vojislava, with whom he had two sons:

Stephen Kulinić, the following Ban of

Bosnia

A son that went with the Pope's emissaries

in 1203 to explain heresy accusations against Kulin

Legacy

and folklore

As a founder of first defacto

independent Bosnian state, Kulin was and still is highly regarded among

Bosnians. Even today Kulin's era is regarded as one of the most prosperous

historical eras, not just for Bosnian medieval state and its feudal lords, but

for the common people as well, whose lasting memory of those times is kept in

Bosnian folklore, like an old folk proverb with significant meaning: "Od

kulina Bana i dobrijeh dana" ("English: Since Kulin Ban and those

good ol' days").

Accordingly, in today's Bosnia and

Herzegovina, many streets and town squares, as well as cultural institutions,

and non-governmental organizations, bear Kulin's name, while numerous

culturally significant events, manifestation, festivals and anniversaries are held

in celebration of his life and deeds

Pretplati se na:

Postovi (Atom)